Types of ZSR

Urbanisation and amenities

How ZSR can be implemented:

- Construction of road, rail, telecommunication and other infrastructure networks serving SEZs should consider transport and communication needs of local communities.

- SEZ construction should be accompanied by appropriate development of residential spaces and associated commercial services.

- The development of key infrastructure and amenities, especially roads, electric streetlights, utilities, education and healthcare, should be extended into local villages, with the emergence of “off-grid” urban villages to be avoided.

Overview of the problem:

The construction of SEZs changes local areas and landscapes through the development of industrial and residential districts, the construction of transport infrastructure and the establishment of other urban amenities. The construction of strong transport links – in particular, roads – has positive impacts for the connectivity of local areas. Many but not all zones have good existing or developing links with rail networks or ports to support the movement of goods. Local populations can also benefit from such improvements in infrastructure, especially if their needs are factored into zone planning and development.

There is a wide variety of outcomes relating to urbanisation and amenities. Enhanced connectivity can generate agglomeration effects, as it becomes easier for people to move into the area. Some zones foster urbanisation and the commercialisation of land in the area, with impacts for neighbouring towns and villages. In many but not all cases, residential areas emerge, often with better civic amenities such as roads, housing, utilities, sewerage, green spaces, schools and hospitals, making the area more suitable for living. However, other zones remain as industrial enclaves or remote outposts, with limited upgrading of local areas.

Even where local areas are upgraded, not all existing communities benefit. While some villages within zones gain from associated urbanisation and amenities, others may remain “off-grid”, experiencing limited or no improvement. Some amenities made available through zone development, such as new health facilities, schools, housing developments and leisure spaces, may be targeted at wealthy investors, incoming white-collar employees and international migrants, but are inaccessible to local populations.

Examples:

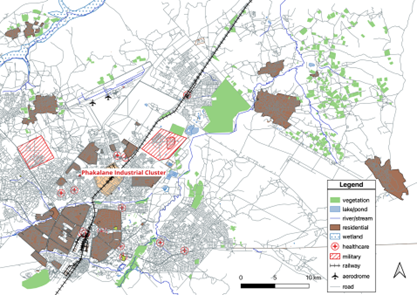

The Phakalane Industrial Cluster in the Gaborone district of Botswana clearly illustrates how urbanisation of the region where SEZs emerge affects neighbouring towns and villages. The zone was set up in 2009 on the site of a small existing industrial cluster. A residential area has since emerged in the neighbourhood, and Gaborone district has become a manufacturing hub drawing migrants from other parts of Botswana. The incoming population has settled in rural areas on the periphery of Gaborone, leading to the creation of ‘commuter’ or ‘satellite’ towns with rental spaces and a lower cost of living – resulting in rural settlements that have been largely agricultural assuming urban characteristics, such as commercialisation of land for rental markets (Sebego & Gwebu, 2013). The images below show the area’s urbanisation.

Road, rail and transport networks with built-up areas around Phakalane Industrial Cluster

Source: GIS mapping, King’s College London

From existing industrial cluster in 2005 (top) to full industrial, commercial and residential complex in 2024 (below): Phakalane Industrial Cluster

Source: Google Earth Pro (Maxar Technologies, 2024; Airbus, 2024)

Private ownership of Sri City in Andhra Pradesh, India, means that zone developers are responsible for all administration, amenities and security for the whole area (Sivaramakrishnan, 2009). This development of industrial and urban infrastructure without significant public expenditure might be seen as an advantage for central and/or local governments (Sood, 2015). However, lack of state investment may lead to slow growth of the SEZ, and, since business needs take priority, result in a lack of local-community-oriented equitable development. Those villages nearer to Sri City’s factories have benefited from new infrastructure and amenities, as well as corporate social responsibility activities, while their more remote counterparts have remained “off-grid”, with under-resourced rural governments continuing to shoulder responsibility for provision of roads and other amenities (Kumar, 2018). Moreover, whereas other Indian SEZs have derived significant new livelihoods opportunities for locals from large-scale in-migration, the concentration of migrant workers in company hostels outside Sri City has made it difficult for urban integration and related shifts in livelihoods to take place.

The case of China:

In China, the state has primarily been responsible for the development and operation of SEZs. Urban land is owned by the state, and villagers own rural land collectively. Local governments requisitioned rural land, transferring it to the state, and changing categorisation of the land to “urban”, which made it possible to sell rights to develop the land. However, the state retained ultimate ownership and responsibility for planning, infrastructure construction and administration of the zones (Zhang, 2011). Many of the early SEZs in China were strategically located in under-industrialised, peripheral areas to promote their development.

The state-led nature of SEZs in China also made it possible to develop large areas of land in anticipation of future industrial, residential and commercial expansion. Many zones were planned for the long-term, divided into clearly demarcated sectors and functions, and provided with considerable infrastructure before the establishment of factories. Chinese zones were typically designed as integrated townships incorporating residential, social and commercial amenities from the start, including separate districts for residential buildings, commercial centres and shopping malls, training facilities and schools, and leisure and recreation facilities, all closely connected to the industrial sites (Goodburn & Knoerich, 2022).

Although rural housing land was not generally acquired for development, to avoid having to relocate village settlements, the Chinese pattern of large city-style SEZs necessitated the incorporation of rural dwellings into the zone area. This led to “villages within the city”, or urban villages, surrounded by high rise developments. These villages remained collectively owned, sometimes for decades, before being incorporated into municipal governance structures, and were often essentially “off grid”; that is, responsible for their own provision of amenities, utilities, roads, waste disposal and even policing. Some became known for illegal drugs, gambling and prostitution, as well as rampant construction in breach of planning laws. Since the 2010s, many have been targeted for redevelopment in an effort to transform urban spaces seen as dirty, chaotic and substandard (Bach, 2010; O’Donnell, 2021). This has generated new rounds of contestations over dispossession and compensation.

China-associated zones overseas

In China-associated SEZs in the rest of the world, China has often promoted the establishment of township-style zones that the country has used domestically. For example, the layout of the Lekki Free Zone in Nigeria represents a typical Chinese-style development plan, planned by Chinese urbanists and executed by Chinese construction companies (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). The quadrant is based around a symmetrical central axis with an exhibition centre, large plots with substantial setbacks, and a man-made lake, as shown in the image below.

Lekki Free Zone southwest quadrant masterplan

(Source: lfzdc.org)

Similarly, for Liaoshen Industrial Park, the masterplan was designed by China’s state-owned China Northeast Architectural Design and Research Institute, and loosely modelled on several economic zones in Liaoning province. The layout represents a typical Chinese-style zone, with a central axis, two centres and multiple nodes (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). Such zones have sometimes been designed without much input from the host country side, leading to difficulties in fitting into broader local urban planning goals for the region.

Liaoshen Industrial Park masterplan

(Source: uslip.com)

Further reading

Goodburn, C., Knoerich, J., Mishra, S. & Calabrese, L. (2024). Zones of Contention. www.kcl.ac.uk/lci/assets/2024/zones-of-contention.pdf

Jenkins, R., Kennedy, L., Mukhopadhyay, P., & Pradhan, K. C. (2015). Special Economic Zones in India: Interrogating the Nexus of Land, Development and Urbanization. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 6(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425315585426