Types of ZSR

Pollution

How ZSR can be implemented:

- SEZs should develop clear plans and approaches to mitigate air, water and soil pollution during both construction and operation phases.

- Regulations should support efforts to reduce environmental pollution and increase the sustainability of SEZs, for example by easing bureaucratic hurdles to achieving such outcomes.

- Regulators should specify due diligence requirements and carry out genuine, independent environmental impact assessments (EIAs) to verify the efforts made by SEZs on environmental and sustainability issues.

- Compensation should be offered to those whose livelihoods are affected by SEZ-related pollution. Companies investing in the SEZs should be encouraged to support affected locals through corporate social responsibility activities.

- Appropriate and coordinated procedures for waste management and treatment should be developed, both within the SEZ and in the surrounding areas. These should be subject to regular monitoring and should include sustainability considerations such as maximising recycling, promoting composting and generating energy from waste.

- Skills training for local communities should include safe collection and recycling of non-hazardous SEZ waste and related entrepreneurial opportunities. Beneficial relationships should be established between SEZ firms and local communities for the supply of recyclable waste.

Overview of the problem:

SEZs attract investment into sectors that are likely to create large amounts of pollutants and industrial waste. Because zones may have specific exemptions from various forms of national regulation, in order to induce investors, national level environmental regulatory bodies may be unable or unwilling to identify and check such pollution and waste, which can lead to serious consequences locally, nationally and beyond. Air, water and soil pollution are all serious concerns during the construction and operation of SEZs, as is waste management.

ansportation, all of which can harm air quality, especially in Port-SEZs with heavy traffic of shipping vessels. Developing countries may lack resources, green technology and equipment to manage the resulting pollution effectively, or to afford less polluting alternatives. In the case of investments from overseas, imports of machinery may include older, more polluting and less energy-efficient equipment that would not meet current environmental requirements in the country of origin.

Water pollution, especially industrial wastewater, can affect the quality of both soil and groundwater, which in turn can cause disease and aggravate existing health issues in the region’s people and livestock. The quality of raw food (including especially agricultural products and fish) may be negatively affected by discharge of toxic waste, potentially leading to biomagnification of toxins in the food chain. Water pollution is also economically damaging in the medium- to long-term, as it lowers the quality of commercial crops, livestock and fisheries and damages livelihoods locally and beyond.

The disposal of solid waste and promotion of recycling is also a challenge in SEZs. In many SEZs, material transported out of the zone is deemed to be an export and is thus subject to import duty. This prevents the effective removal of waste from SEZs, and may lead to excessive landfilling or dumping within the zone itself. It also prevents the efficient processing and re-use of scrap materials, which could also provide an income-generating activity and a source of sustainable alternative livelihoods for local communities. SEZs often do not manage solid waste in an ecologically sound manner, and SEZ waste management regulations frequently do not require sustainable recycling, composting or waste-to-energy practices. Waste may be dumped in local landfill sites, where the handling of hazardous components may prove to be a health risk for informal rubbish collectors and local residents.

Increasing urbanisation around SEZs also leads to increasing pressures on local ecosystems, with in-migration and the rapid growth of local districts generating increasing amounts of solid and hazardous waste that may be beyond the area’s current capacity to treat effectively.

Examples:

While the Djibouti International Free Trade Zone and Port is located in a desert with little urbanisation beyond the premises of the Zone, increased traffic in shipping vessels causing excessive smoke pollution has decreased air quality, and the local port authority is reportedly struggling to manage air pollution (Crossley, 2023).

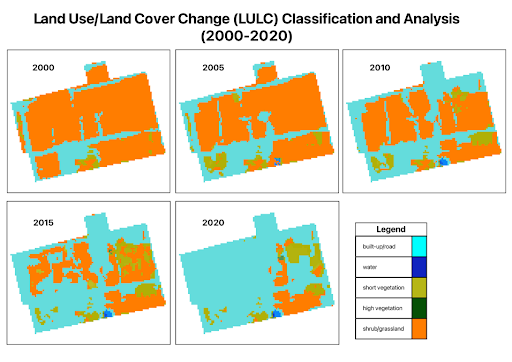

The wastewater from textile factories in Ethiopia’s Hawassa Industrial Park has polluted the Boicha stream and a biological lagoon nearby. Those living downstream from the water bodies have been most severely affected, as they use the water for drinking, irrigation, domestic purposes and rearing livestock. As cattle also drink the polluted water, this has affected dairy produce from the region (Bekele et al., 2021). One study found heavy metal pollution high enough to cause irreversible damage through neurological issues, kidney failure or cancer in those who consume water or fish from these sources (Bekele et al., 2020). There is at present no mechanism in place to monitor soil quality regularly or evaluate the consequences for people in the area as a result of water and soil pollution. In the image below, Hawassa Industrial Park can be seen to expand from 2000 to 2020, growing closer to the water bodies to the south.

Land use and land change for Hawassa Industrial Park (2000–20)

Source: GIS mapping, King’s College London

Due to the construction of Lekki SEZ and deep-sea port near Lagos, fish caught in the area are often toxic and inedible, with signs of severe water pollution (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). Sources of this pollution include discharge from ships as well as spills of oils, lubricants, fuels and other liquids. Some of these liquids may come directly from the zone, since satellite imagery has identified that Lekki industries have two main drainage channels where they dispose of industrial wastewater into the sea (Adeyemi, 2023).

Waste management has also been a problem for the Lekki Free Zone. Since the SEZ operates autonomously, Lagos Waste Management Authority lacks jurisdiction and can enter only at the invitation of zone or firm managers, making it difficult to monitor environmental or waste disposal compliance. The zone produces various types of industrial waste requiring special handling, which has mostly been taken to the Epe Landfill area by a network of small private contractors, each operating independently and contracted directly by the factories (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). However, due to the landfill’s recent closure, there is an urgent need for an alternative disposal site with proper monitoring of waste management. An additional concern relates to communities resettled from the area of the zone, which do not have reliable waste collection in their new locations, particularly for food- and agriculture-related wet waste, suggesting an environmental dimension to the extensive land expropriation in Lekki.

One area of environmental contention is the mining of sand from Uganda’s lakes, rivers and swamps to support construction and industrial manufacturing in Liaoshen Industrial Park, particularly in the ceramic tile industry. Sand mining in Lake Victoria has been especially controversial, with reports of illegal dredging and discharge of waste waters into the lake, but wetlands elsewhere across Uganda have also been negatively affected, in particular those in Lwera (Monitor, 2021) . These wetlands provide water to a large population, and trap silt and other pollutants, thus making an important contribution to public health. Industrial pollution of nearby rivers, including most notably the Mayanja, which flows into Lake Victoria, is also a concern. In 2021, a new water supply system in Nakaseke, aimed in part at improving water availability in Liaoshen Industrial Park, was in development, while the construction of a water treatment plant inside the park itself was underway in early 2024 (Monitor, 2024).

Air pollution has also increased with the operation of factories in Liaoshen Industrial Park, as well as the dumping of waste materials, especially plastic bags, in the soil around villages. Liaoshen management confirmed that individual factories were responsible for the removal and disposal of their own waste with a lack of park-level coordination (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). One positive outcome is that some villagers around the park have begun engaging in scrap recycling and commercial use of factory waste products, including rags, plastics and oil, which may provide alternative sustainable sources of income in the longer term.

Egypt’s TEDA-Suez SEZ has demonstrated basic levels of environmental compliance (Springer et al., 2023). Any firm wishing to build a factory in the zone must obtain an environmental permit from the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency before it can start construction. The permit is based on water use, land use and impact on biodiversity and energy consumption. Only after a full environmental assessment can construction begin. Moreover, firms in the zone are subject to annual audits and inspections from local authorities and are required to reapply for environmental permits on a regular basis. Firms in the SEZ met these minimum domestic requirements, which are however not up to the level of international best practice.

TEDA-Suez SEZ has also demonstrated effective response to environmental breaches. In 2015 a paper factory in the SEZ was found to be dumping contaminated water and hazardous chemicals into the Suez Canal, in contravention of environmental regulations. An internal investigation led the factory to end this pollution, and SEZ management introduced more frequent inspections as well as raised the wastewater treatment capacity of the zone (Springer et al., 2023).

An innovative closed system of environmentally sound waste management has been established in Noida SEZ near Delhi, solving a long-entrenched challenge of how to handle SEZ waste. According to the Indian 2005 SEZ Act, transferring goods, including many forms of waste, from within an SEZ to other parts of India is perceived as an “import” and is liable to be taxed. This includes even some types of waste created in the SEZ, creating a disincentive to process this waste outside the SEZ. To address this problem, Noida SEZ has set up a waste management unit inside the zone, operated by Vedika Infracon with support from the local government. The unit, which operates at a profit, uses vehicles to collect all types of wet and dry waste from the zone’s factories, then segregates, presses, composts and recycles it on-site. The recycled waste is used to create new commercially viable products such as plant pots and compost, for use within the zone (Vedika Infracon, 2024).

The unit has hired migrants from other parts of India who previously worked as ragpickers in informal and precarious conditions outside the zone, and trained them in professional waste management. Provided with a regular salary, a uniform and on-site housing, these new waste managers have experienced considerable gains to their livelihoods and status.

Polepally SEZ in Telangana state was established in 2006 with a focus on pharmaceutical manufacturing. The discharge of toxic effluents from its factories had made groundwater unusable by 2017. The villagers ceased using it for drinking as well as for agriculture (Agarwal, 2018). Hired farm hands now demand higher wages to work in contaminated farms in Polepally, because of the risk of health hazards. Farmers from four villages near the zone have protested over land degradation, declining agricultural produce and dying cattle, Recent tests suggested that soil in the areas surrounding the SEZ had become alkaline, and contained high levels of zinc, carbon, and potassium (Kashyap, 2022).

The case of China:

In China, massive environmental degradation and pollution of air, water and soil has occurred on the back of its successful industrial development, including the activities of factories in its SEZs. While SEZ-specific impacts cannot be disentangled, problems are felt up to the present day, are continuing, and the damage will take decades to resolve. The health consequences in particular have been severe, leading to a massive accumulation of associated diseases amongst the Chinese population, especially spiralling rates of cancer diagnoses (Li et al., 2016).

China-associated zones overseas

A recent cross-country study of Chinese projects in Africa, including SEZs, suggested that these often do not meet the standards of China’s recommended Green Development Guidance (Springer et al, 2023). Instead, Chinese firms tend to adhere to the host country’s minimum environmental standards, including on pollution, while taking advantage of regulatory gaps.

Further reading

Springer et al., 2023. Elevating ESG: Empirical Lessons on Environmental, Social and Governance Implications of Chinese Projects in Africa https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2023/08/GCI_GIZ-Report_2023_FIN.pdf