Types of ZSR

Food security

How ZSR can be implemented:

- Development of industries and construction of ports should take account of the reduction in and pollution of local agriculture and fishing, with mitigating measures to be implemented where necessary.

- Local replacements should be found, insofar as possible, for agricultural lands and fishing territories that are lost or severely negatively impacted by SEZ and port development.

- Compensation should be offered to those whose livelihoods are affected by the changes in availability and prices of food caused by SEZ construction and operation. SEZ firms should be encouraged to support affected locals through corporate social responsibility activities.

- Farming or other food-production use of SEZ land should be encouraged to continue until lands are needed for factory construction, and former agricultural lands should not be left idle for long periods in anticipation of future industrial use.

Overview of the problem:

Land used for farming or coastal terrains used for fishing is are often absorbed in large scale industrial projects such as SEZs. This naturally leads to change of land use from agriculture to industry. Construction along the coast leads to changes in the nature of the waves, potentially reducing the catchment area for fishers.

This can result in a reduction in farming in the area and negatively impact local fishing catches. Water Soil and soil water pollution from industries can also affect the quality of agricultural produce and fish. Food-related production such as farming, fishing, beekeeping and livestock rearing must adapt to the changing circumstances.

This situation, as well as the loss of access to foraged wild foods, can negatively impact people’s dietary patterns and quality of nutrition intake. Inferior quality food may replace fresh produce, resulting in nutritional deficits. As local cultivation and farming declines, food and agricultural goods become less available from local sources, with grains, fresh fruit and vegetables having to be transported in from afar, reducing the freshness and quality of food and increasing food prices.

Examples:

In the Kribi Deep Sea Port, locals saw a decline in fishing of nearly 50 per cent in some cases due to port infrastructure making the sea more turbulent (Toto, 2024). Such a steep decline has inevitable impacts for diets and food security in the region.

In Nigeria’s Lekki SEZ and port, both farming and fishing have collapsed, due to the reduction in agricultural land resulting from the establishment of the SEZs and the impact of the Lekki port. Fish have become much scarcer, obliging local fishers to fish more frequently and further from shore in more dangerous waters. Some fishing communities have moved inland, to the Lekki lagoon, but even there, fish have disappeared. Palm and coconut trees have also died since the drying of two lakes, harming the local trade in coconuts and palm kernels on which many locals depended (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). The long-term damage to the local ecosystem has also created significant damage to local livelihoods, with many people no longer able to depend on fishing or coconut or palm farming.

The inevitable result has been a decline in sales of local agricultural produce in local markets, and a decrease in healthy and fresh produce available for natives of Lekki. Former farmers must now travel long distances to Epe or Ijebu to buy fruit and vegetables, or food must be brought in from villages further from the zone, with locals complaining that these vegetables are intensively farmed with heavy chemical use, and the fruit is not fresh. Food prices have increased following establishment of the zones and port, and there has been an increase in consumption of dried and packaged foods (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024).

Uganda’s Liaoshen Industrial Park provides a rare example of a zone with a positive impact on local agriculture. No financial compensation was provided for those evicted from the land when the zone was set up in 2015, but villagers received new plots nearby that were typically larger than their former land, as well as free maize seed and the promise that their maize crops would be purchased at least market rates, to be processed in the new industrial park. This incentivised rural people to continue farming, and the land under cultivation across Nakaseke District increased from 974km2 in 2016 to 2,083km2 in 2023 (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). The most major increase was in maize farming, because of enhanced investment in maize storage and processing facilities in the industrial park.

Other forms of agricultural production across the district increased too, including pineapple and mango growing for processing in the park, as well as livestock keeping, fish farming and beekeeping (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). The influx of migrant workers also provided an enhanced market for food crops, especially fruit and vegetables, in local markets, leading to improved incomes from farming and the avoidance of food security concerns (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024).

The risk of further industrial park expansion has pushed some tenant farmers into growing annual crops that could be grown and harvested quickly should they be given notice of eviction, leading to a small-scale shift from, for example, slow-growing coffee, bananas and mangoes towards faster maize, pineapples and beans (Goodburn, Knoerich, Mishra & Calabrese, 2024). Overall, though, the short-term impacts of the park have been extremely positive for local agricultural livelihoods, not only through the ready supply of land and seed, but also through the improved agricultural markets and enhanced facilities for processing food products locally within Liaoshen Industrial Park. Whether or not these positive impacts can be sustained in the longer term, particularly with further expansion of the park and a diminishing supply of available land, remains to be seen.

The environmental and social impact assessment conducted for South Africa’s Musina-Makhado SEZ failed to analyse correctly the impact on local women’s livelihoods, which relied on wild-sourced food such as Mopane worms. The construction of the SEZ led to the dramatic decline in these food sources, and prevented the empowerment of women through entrepreneurship in the emerging market for insect proteins. Other species of caterpillars are also found in the Limpopo region, along with termites and tree products such as baobab and marula fruit, as well as mopane essential oils – all of which were important for local livelihoods. (Dzerefos, 2024).

Food security in affected households in Polepally SEZ, in India’s Andhra Pradesh, has been dramatically altered since the establishment of the zone in 2007. The population of former farmers depend increasingly on food grains procured from the market, which require cash incomes not sufficiently available to many. Acute temporary shortages have become a common problem (Rawat, Bhushan and Sujata, 2011). A particular area of concern has been the quality and quantity of food available to women and children, who are often the hardest hit by household food insecurity in India.

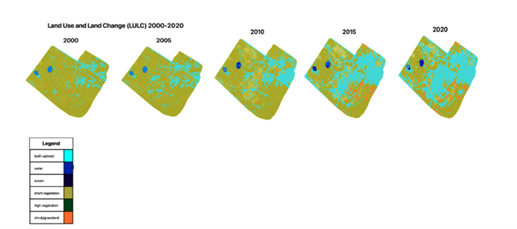

There has been a drastic reduction in farmland upon the establishment of the Luanda-Bengo SEZ. Agricultural land was replaced by built-up areas of the zone (see image below), with potentially severe impacts on the provision of food crops including maize, cassava, sweet potatoes and beans.

Land use and land change at the Luanda-Bengo SEZ (2000-20)

Source: GIS mapping, King’s College London

The case of China:

China’s rapid SEZ growth in the 1980s and 90s, especially in Shenzhen, gave rise to concerns about the diminishing quantity of arable land in the region and more broadly across the country, as urbanisation and industrialisation soared. By 2006, the ecology of 60% of China’s territory was considered fragile; 90% of natural pasture land faced degradation; 60% of China’s wetlands were inadequately protected; and food security became a major state concern (McBeath & Huang McBeath, 2008). To safeguard food production, the central Chinese state set a limit on the minimum amount of cultivatable land, tightened regulations on land conversion, and sought ways to increase the amount of arable land. More recently the Chinese state’s focus of attention has been on increasing land use efficiency, for example by improving cultural practices of farmers, and introducing improved seeds and crop enhancers.

Initially, Chinese SEZs faced difficulties in the provision of fresh food within the zones, owing to the strict demarcation of export-oriented production and domestic manufacturing, via an internal border that local farmers were unable to cross even to supply goods (Bach, 2019). By the mid-1980s, with agitation from both farmers and SEZ residents, permission to cross the internal boundary was granted to villagers for the sale of food produce inside the SEZs, with Shenzhen’s “agricultural gates” particularly well known (Ma and Blackwell, 2017). Ultimately, such boundaries were completely abolished, and China’s newer economic zones do not have an internal border. Supplies of agricultural goods can thus easily be brought into the zones ensuring consumption of fresh grains, fruit and vegetables can be maintained

China-associated zones overseas

Compared to other SEZs, China-associated zones do not seem to fare significantly better or worse in terms of outcomes for food security. In order to attract Chinese capital, host nations may liberalise regulations with little attention to the potential reduction in farming area or fishing catchments, yet agricultural livelihoods may be at least as severely damaged by domestic projects, including for example the Nigerian-owned Dangote oil refineries in Lekki, which have had a worse impact in comparison with the Chinese quadrant of the zone (CAPPA, 2023; The Guardian, 2024). Some China-associated zones can in fact have an overall positive effect on food security, such as in the case of agricultural-processing SEZs or industrial parks, which encourage local farmers to enhance production and connect smallholders to global value chains, thus increasing their income as well as creating more related off-farm jobs, without having to abandon agriculture (Kladaki & Cai, 2020).

Further reading

Kumar, V. (2014). SEZs and Land Diversifications: Need for an Alternative Model. Journal of Economics and Development Studies, 2(3), 215-224.

Doss, C., Summerfield, G., & Tsikata, D. (2014). Land, gender, and food security. Feminist economics, 20(1), 1-23.